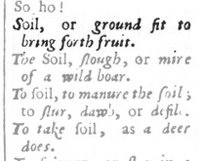

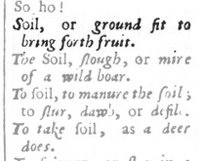

Dating to the dawn of the 18th century, this may well be the first dictionary definition of soil. And a beautiful bit of prose it is. A term reserved for the good stuff, the definition has a hint of awe, of appreciation, of desire even. And of simple mystery.

At a time when the definition of soil has achieved some ambiguity, and some of us exclude lunar soil from "real" soil, I am intrigued by these old definitions.

Reading further in John Kersey's "A New English Dictionary", one finds that the ground meant earth. It also meant "the foundation of a thing". If he had chosen to use earth instead of ground, JK would have changed the meaning of soil to one less involved with our daily interaction. Was this an intentional distinction?

His meaning of fruit includes benefit. ''Fruit of the earth" and "first fruits" were common and established terms. JK has "first fruits" meaning "...profit of a spiritual living". At a time when we suppose the concept of soil to have been simple, why didn't JK keep the definition of soil simple and agronomic, unencumbered with spiritual and beneficiant tones? I find his wording wonderfully rich with subtle allusion.

Soils are commonly understood as materials with a capacity for plant productivity. That is too broad. Most soils have a history that includes alteration by living processes, a history that separates soil from non-soil material. Further refinement of the soil concept is occurring in view of an appreciation of energy transport and transformation within soil. Accurate to this unfolding understanding of soil is Nikiforoff's 1959 definition of soil as the "excited skin of the subaerial part of the earth's crust". Soil is a product of solar radiation. From this perspective the concepts of lunar soil and of martian soil are not so inconceivable.

John Kersey's dictionary is recognized as the first work that incorporated all words of important common usage. Prior to this work, dictionaries concentrated on difficult and obscure words. This is according to "Chasing the sun: dictionary makers and the dictionaries they made" by Jonathon Green. I turn the pages of JK's work and I sense tremendous care in his choice of words. In the case of soil, he relied on rich allusion to gently convey something of the knowing that he and his fellows had about this dark and excited resource. His definition of soil thus stands the test of time as well as, and perhaps better than, many that have been been written since.

Soil scientist George Demas (28 April 1958 - 23 December 1999) pioneered the study and classification of subaqueous soil. He passed away on this day seven years ago. His award winning work advanced the understanding of soil genesis and morphology sufficiently that USDA soil taxonomy required revision. George Demas' death occurred shortly after the importance of subaqueous soil became accepted. His sudden and untimely passing is a great loss to his family of colleagues and friends.

Soil scientist George Demas (28 April 1958 - 23 December 1999) pioneered the study and classification of subaqueous soil. He passed away on this day seven years ago. His award winning work advanced the understanding of soil genesis and morphology sufficiently that USDA soil taxonomy required revision. George Demas' death occurred shortly after the importance of subaqueous soil became accepted. His sudden and untimely passing is a great loss to his family of colleagues and friends.-25+010.jpg)